The day it became real

There is a world of difference between saying yes to brain surgery and living through it. Between the moment you sign the consent form and the moment you find yourself on a gurney at five in the morning in a corridor outside the operating room. This post is about that passage. The moment when "someday" becomes "it's tomorrow," and when "it's tomorrow" becomes "it's now."

From "someday" to "it's tomorrow"

For months, the operation is a concept. Something that will happen, later, someday. You talk about it, you prepare intellectually, you read, you ask questions, you try to picture it. But it remains abstract. It is in a future distant enough not to feel entirely real.

And then the calendar moves forward, and the future draws closer. The date is set. January 30, 2025. It is three months away, then one month, then two weeks, then one week, and one morning you wake up and realize it is tomorrow. And then it is not abstract at all.

The bungee jump, once again. Except this time, you are standing on the edge of the bridge, your feet over the void, and it is no longer a question of thinking about it. It is a question of jumping.

The apprehension, and its disappearance

The apprehension built up gradually over weeks, like a rising tide. A constant, underlying worry that colors everything. Everyday actions become strange because you know that soon it will be the last time you do them with this brain, in this state. Soon, there will be electrodes inside it. Soon, something will have changed irreversibly.

And then, curiously, the night before the operation, the apprehension vanished. Just like that. Not gradually, not after a long process of rationalization. It left, and it did not come back until the anesthesia. Yes, you could die. Yes, you could wake up a vegetable. Yes, everything could go wrong. But you have put all your affairs in order. Everything is tidied up, everything has been said, everything has been planned for. If something happens, the people you love will know what to do. And that certainty, the certainty of having prepared everything, releases an unexpected calm. It is not recklessness, it is serenity. The serenity of someone who has chosen, who has prepared, and who is ready.

The departure for Paris

The departure was a moment in itself. Leaving the house, hitting the road, arriving in that immense city with that immense appointment waiting. Knowing that you will not come home the same person. That something definitive will happen between the moment you walk through the hospital doors and the moment you walk out again, days later, with metal in your skull and a device under your skin.

There is a strange solemnity to that journey. You watch the landscape rush by with a detachment you cannot explain, because the choice has been made, it is the right one, and the only thing left is to see it through.

Trusting

In the days leading up to the operation, I was accompanied by the chaplaincy at Pitié-Salpêtrière and by the Maronite parish. I will not dwell on this point because faith is something deeply personal, but I want to mention it because it matters. When you are about to entrust your brain to someone, there comes a moment when science, statistics, and rational explanations are no longer enough. You need something else. You need a form of trust that goes beyond the medical, that touches something deeper. For me, that is where it came from.

And that is perhaps the most important word in this entire post: trust.

Trust in the surgical team, in Pr Karachi, in the people who will be handling your brain for hours. Trust that you made the right decision, that the tests were done correctly, that the indication is solid. Trust in your own body, in its ability to withstand what is about to happen to it. And trust in something greater, whatever form that takes for each person.

Without that trust, you do not jump. You stay on the bridge. And I jumped.

The morning of January 30

In the morning, you wake up a little worried. That is an understatement, obviously, but it is also the truth: it is not terror, it is a quiet worry, the worry of someone who knows what awaits him and has decided to go through with it anyway. You get up, you get ready, you walk toward the operating room. The corridors are long, the lights are white, and the world gradually narrows down to a single point: the moment you will fall asleep and it will be in someone else's hands.

The anesthesia. They talk to you, they insert the needle, you might count, and then nothing.

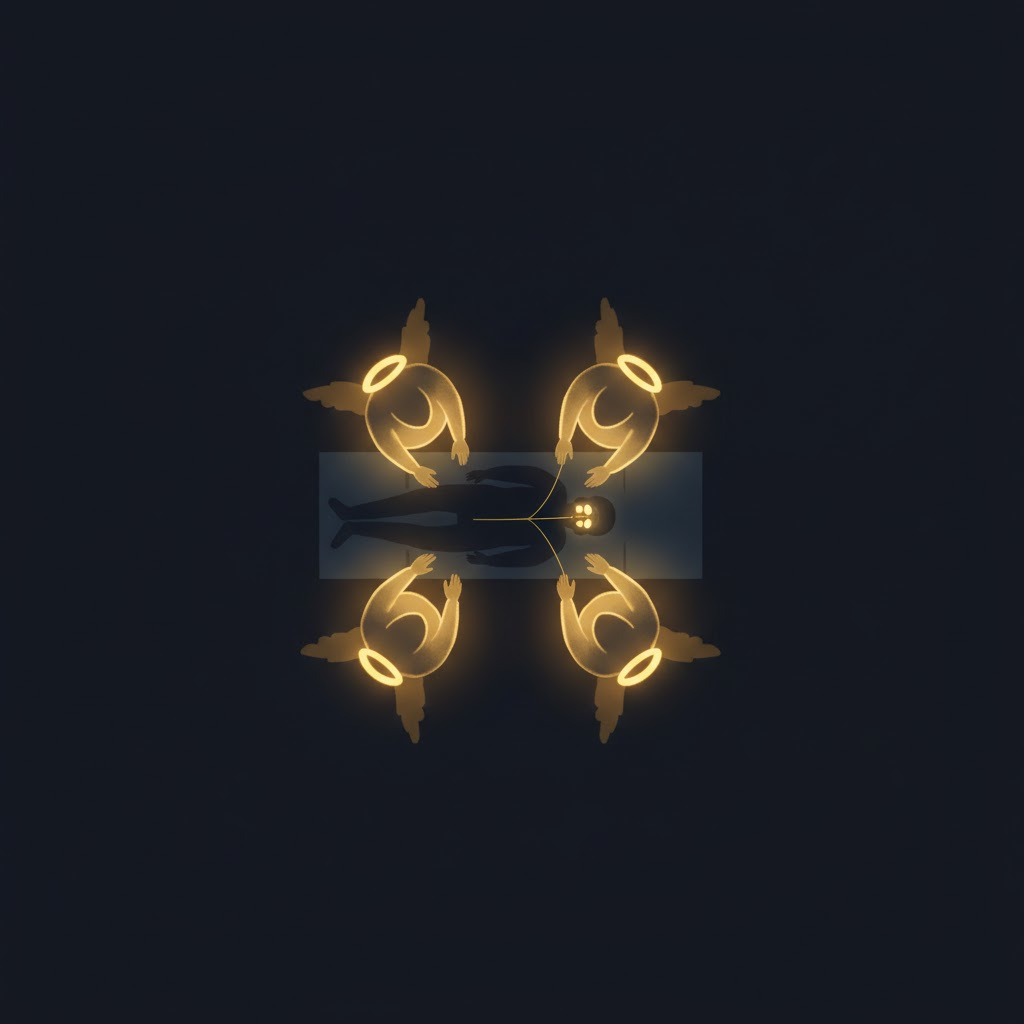

Four angels

And then, a moment later, you open your eyes.

There are silhouettes around you. Four faces, blurry, luminous, looking at you. For a split second, you wonder if they are angels. And then you understand that no, you are not dead, you are in the recovery room, and those four people are caregivers checking that everything is all right.

After that, everything moves very fast and very slowly at the same time.

You vomit. Once. Then a second time. Then a third. Your head hurts, which, when you think about it, makes perfect sense for someone whose skull has just been drilled open. The gurney is too small, the bed is too small as well, and you have to get from one to the other as best you can, half dazed, your body heavy and your head a mess. You vomit again. You lie down. You close your eyes.

And then you realize: it is done. You are not dead. You are not a vegetable. You are there, very much alive, with a colossal headache and vomit on your hospital gown, but alive.

More alive than ever

What went through me in the hours after waking up was a feeling I had never experienced before: the feeling of being more alive than ever. Because I had just voluntarily gone through what could be the worst thing that could happen to someone. I had accepted having my skull opened, having electrodes planted in my brain, knowing the risks, knowing what could go wrong, and I was on the other side.

There is probably a quasi-masochistic streak in the way I function. My motivation has always been fueled by difficulty, by doing what people told me was impossible. But this time, it is different. This time, I know it with absolute certainty: I will never be able to do anything harder than what I have done. Apart from cancer, a cardiac arrest, or a serious accident, nothing in my life will ever be more grueling than what I went through that day.

And that certainty changes everything. My life is complete. Not in the sense that there is nothing left to do, but in the sense that the hardest part is behind me, and everything that comes after is a bonus. I see things very differently now. I put things in perspective much more. Everyday problems, frustrations, obstacles, all of that weighs infinitely less when you have looked death in the face and told it no thanks, not today.

What happened while I was sleeping

From the neurosurgeon's perspective, here is how that day went.

First, general anesthesia. I was put fully to sleep, because unlike some deep brain stimulation procedures that are done while the patient is awake, mine was done under total anesthesia.

Before anything else, a stereotactic frame is fixed to the skull. It is a rigid metal device that is literally screwed onto the head and serves as an absolute reference for all the measurements and trajectories that follow. It is a somewhat brutal step, but generally you could not care less, since you are asleep.

Next, an intraoperative MRI. The brain is imaged in real time to calculate, with millimetric precision, the trajectory the electrodes must follow to reach their target: the globus pallidus internus, on both sides.

Then comes the procedure itself. The skull is drilled, a passage is opened through the bone, and the electrodes are lowered along the calculated trajectory, millimeter by millimeter, with micro-recordings taken along the way to ensure the correct position.

And this is where it gets fascinating. To verify exactly where to place the electrodes, the team slightly lightens the anesthesia. Just enough for the GPi to resume some activity, for it to start sending its erratic signals again. It is a bit like hunting a fly with a swatter: you know it is in the room, you have a rough idea of where it is, but to hit it you need it to move. So they wait for the GPi to show itself, they watch for a spike of irregularity in the signals picked up by the electrodes, and the moment it appears: they map it. They know they are in the right spot, they lock in the coordinates, and the electrodes are secured in their final position.

Verification. They check that everything is in place, that the electrodes are where they should be, that nothing has shifted.

Next, a change of configuration. I am repositioned for the second part of the procedure: the implantation of the pulse generator, the device that will power the electrodes with electrical current. The site is prepared at chest level, on the left side, a pocket is created under the skin, the pulse generator is placed inside, and it is connected to the electrodes via cables that run under the skin of the neck.

And that is it, it is over. They close up, clean up, and let the patient wake up. The patient in question is me, and he vomits three times before realizing he is not in paradise.

Behind this technical description lies a surgical gesture of rare virtuosity. Pr Karachi operates with a precision that commands respect. Navigating through the brain, millimeter by millimeter, aiming for targets a few square millimeters wide buried deep within the basal ganglia, adjusting trajectories in real time based on captured signals: this is an exercise of absolute exactitude, where the slightest error can have irreversible consequences. And she does it with a mastery, a confidence, and an elegance that border on art. This is not surgery, it is goldsmithing.

The next post will tell the story of what comes after.

To be continued.