Healing is a strong word

Paris, obviously

I hated Paris before the operation. I hate it even more after. Keep your big cities full of grey, noise, and people who complain.

Picture this: you have just come out of brain surgery, you need rest, calm, silence. And you are in Paris. The noise is permanent, omnipresent, inescapable. Horns, sirens, construction, people screaming in the street at three in the morning. And in my case, a trumpet-playing neighbor. Because of course.

I was supposedly in a quiet area, near the hospital. Quiet for Paris means you only hear three sirens per hour instead of ten. The rest that a freshly operated brain needs is not exactly what this city has to offer.

Two months. From early February to late March. Two months in a home that is not yours, in a city that wishes you no good, waiting for the body to heal and for time to pass.

The bandage

The number one risk of DBS is infection. And I am a conscientious patient: when they tell me "you must" and "it's dangerous," I take it at face value, not as a precaution.

So, the bandage. Fairly large, fairly cumbersome, to be changed every two days. The protocol is dictated by the neurosurgeon, and it is clear. Betadine shampoos, Cicalfate cream, precise procedure, no improvisation. A nurse comes to the apartment for each change.

The first nurse who came wanted to improvise. "Oh, some ointment?" No. No ointment. No variation. No "we do it differently where I come from." The protocol is the protocol, it comes from the neurosurgeon who planted the electrodes, and it is not negotiable. He did not stay.

It is a detail, but it is telling. When you have holes in your skull and electrodes in your brain, you do not want someone "trying something." You want the protocol followed to the letter, by someone who understands why they are there.

The skull, the device, and everything else

Everything hurts, but nothing hurts in the same way.

The skull, first. They drilled your head, screwed a frame onto it, planted electrodes inside. That leaves marks. The scars pull, itch, remind you of their presence with every movement. You learn to sleep in unlikely positions to avoid pressing on the wrong side.

The device, next. That thing under the skin of your chest, that does not really hurt but that is there. Permanently. You feel it when you move, when you bend, when you lie down. It is not painful, it is just strange. A foreign object that is now part of you, and that you will have to learn to live with.

And then the fatigue. Not normal fatigue, the kind you fix with a good night's sleep. Post-operative fatigue, the kind that pins you to the bed without warning, that turns the slightest outing into an expedition, that leaves you breathless after climbing a flight of stairs as if you had run a marathon. The body has been through trauma, and it lets you know.

The diffuse sound and the nausea

At first, it is the pain from the scars and the headache. That, you expect, it makes sense, it is bearable.

Then comes a stranger sensation: a diffuse sound. Not an external noise, not exactly a classic tinnitus either. Something between the pressure of the bandage on the skull, the stimulation running at minimum, and the brain trying to figure out what is happening to it. A permanent background hum, like an electrical appliance you cannot turn off. Because that is literally what it is.

And then the nausea arrives. The early stages of stimulation, even minimal, are no fun. The brain is receiving an electrical current it is not used to, and it protests. Not violently, not dramatically, just enough for every day to have a slightly nauseating taste, a layer of diffuse discomfort that sits on top of everything else.

The panic of the first charge

I need to tell this story, because it sums up the absurdity of convalescence quite well.

The device is rechargeable. You place a charger on the skin, above the device, and you wait. So far, nothing complicated. Except that during charging, the device disconnects from the remote control. And nobody had told me that.

First charge. I place the charger. I pick up the remote to check that everything is fine. No connection. The screen cannot find the device. The device is not responding.

PANIC.

Has it crashed? Has the stimulation stopped? Are the electrodes still powered? Is my brain losing the signal? What is happening? WHAT IS HAPPENING?

Nothing. Nothing is happening. It is normal. The device does not communicate with the remote during charging. That is all. But nobody bothers to warn you, and when you discover this on your own, in a Parisian flat, with electrodes in your brain and zero experience with this device, the word "panic" is an understatement.

Stimulation "emergencies"

Another convalescence discovery: the medical definition of the word "emergency" is not yours.

When something seems wrong with your stimulator, you call the emergency number. You explain your problem. And in the vast majority of cases, they tell you: "Look, you can wait a little. Maybe take some paracetamol."

The only situation that constitutes a real emergency, in the medical sense of the word, is if you have fallen on your head or suffered a head trauma. In that case, they need to check that the electrodes have not shifted. Everything else, pain, strange sensations, worries, apparent malfunctions, falls into the category of "it can wait."

It is probably rational from a medical point of view. But when you have electrodes in your brain and something feels wrong, "take some paracetamol" is not exactly the answer you were hoping for.

Fifteen days without a computer

For someone whose job, passion, and most of their social life revolve around a screen, fifteen days without a computer is long. Very long. Very, very long.

Impossible to concentrate. Impossible to stare at a screen. The brain cannot keep up, the eyes cannot keep up, and in any case, the fatigue catches up with you after ten minutes. So you do nothing. You sleep. You stare at the ceiling. You sleep some more. You try to read, you give up after three pages. You sleep.

This is perhaps the most insidious part of convalescence: the boredom. Not the comfortable boredom of a rainy Sunday, the forced boredom of someone who physically cannot do anything and knows it. The body recovers, the brain recovers, and you are stuck between the two, waiting for it to pass.

Mum

And then there is Mum.

Mum who is there, as always. Doing her best at being a mum, with that mix of total presence and helplessness that has defined her since the beginning of this disease. She cannot heal her son, she cannot take away the pain, she cannot speed up the healing. But she can be there. And she is there.

There is something cruel about being the parent of a sick child. You want to fix everything, and you cannot fix anything. You want to protect, and all you can do is watch. And yet, that presence, that accepted helplessness, that simple act of being there and making you feel loved when you need it: that is perhaps what matters most. More than the medication, more than the adjustments, more than the medical appointments.

Dad goes home from time to time. An aftertaste of boarding school: the back and forth, the logistics, life carrying on elsewhere while you are suspended. My childhood neurologist, now retired, comes to see me. The neurosurgeon, when her schedule allows. Dr Ney, a psychologist of rare humanity, whom I should have asked far more questions.

And then there are the visits. A few friends, family. My uncle, my cousin — who is also my godson — thank you both. People who take the time to come, who ask questions, lots of questions, and that is exactly what I need. I love being asked questions. I love explaining, telling, going into detail. It is my way of processing what is happening to me, and it is infinitely better than the awkward silence of those who do not dare ask.

People who matter, each in their own way, at a time when you feel terribly small.

The return

Flying is forbidden before April. When you live far from Paris, that means an ambulance. Eight hours on the road, lying in the back, body in pieces and head spinning. Eight hours to get home after two months in a city you have never liked.

And then the door opens, and you are home.

Finally.

I slept for two days. Two days straight, in my bed, in my house, in silence. Not the approximate silence of Paris, the real thing. The silence of the countryside, the kind where the only sound that wakes you is a bird, and you could not care less because it is a bird and not a trumpet player.

The countryside and trust

Coming home means getting back what Paris could not offer. Walking outside, in the countryside, with no noise, no crowds, no stress. Resting completely, not halfway, not keeping one eye open, but truly resting. Feeling the body relax in an environment that is not hostile.

But coming home also means moving away from the hospital. And moving away from the hospital means accepting that everything is fine. Trusting. Trusting the device, the minimal settings, the body that is healing, the brain that is adapting. Trusting by force of circumstance, because you have no choice, because the neurosurgeon is eight hours away and the next adjustment is not tomorrow.

I do not like trusting by force. Nobody does. But that is the deal: the peace of home against the reassuring proximity of the hospital. And peace won.

Getting back to work

In June, I went back to teaching. Or rather, I tried to.

One and a half hours. That is what I could manage, standing in front of a class. One and a half hours before the head started spinning, before the nausea came back, before the brain said stop, that is enough for today. Not two hours, not three. One and a half hours, and even then, gritting my teeth.

My students were extraordinary. Their support when I returned, their patience, their ability to act as though everything was normal when nothing was: a huge round of applause and an immense thank you. You do not always realize the impact that the kindness of the people around you has when you are fragile. They did it naturally, and it mattered more than they know.

Three months, eight months

Something needs to be clarified, because the numbers they give you at the hospital do not mean what you think they mean.

"Three months of convalescence." That is what the neurosurgeon says. And it is true, but not in the way you understand it. Three months is the time for the infection risk to become virtually nil. Three months is the point after which you can reasonably consider the scars closed, the electrodes in place, the hardware safe from infection. It is a medical milestone, not a return to normal life.

Eight months. That is the minimum time it took me to be able to resume my usual activities. And even then, part-time. Reduced part-time. Therapeutic part-time, to use the administrative term. Not full-time, not regular part-time: a lightened, supervised, gradual part-time, with the doctor's approval.

I am lucky to have an employer who respects the law. That is not a detail. It is a privilege. Because when you read some accounts, you quickly understand that not everyone is that lucky, and that recovery from brain surgery should never depend on an employer's goodwill.

The tunnel

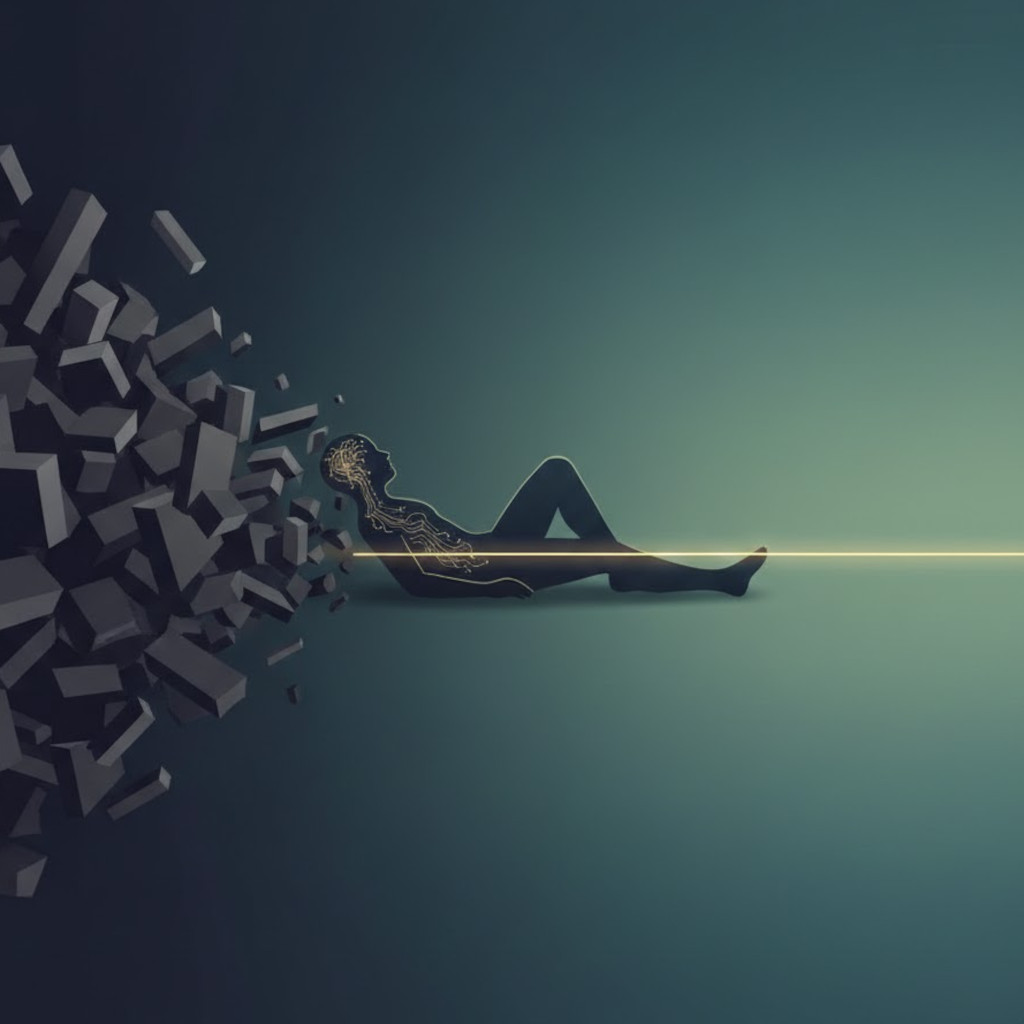

Convalescence has no turning point. No click, no movie scene where the character gets up one morning and feels that everything has changed. It is a tunnel. Long, monotonous, sometimes painful, with a light at the end that you sense more than see.

The stimulation is on, but at minimum. Just enough for the brain to start adapting, not enough for the effects to be spectacular. It is a period of waiting, of patience, of small daily battles against fatigue, pain, and boredom.

You do not heal. You convalesce. And convalescing is a strange state: you are no longer ill in the acute sense, but you are not well either. You are in between, in a no man's land where every day looks like the one before, and where progress is measured in millimeters.

The next post will tell the story of how the brain relearns, and how it resists.

To be continued.