My body doesn't do what I tell it to

I have myoclonus-dystonia. Genetic. DYT11, mutation of the SGCE gene. I was born with it, and I will die with it. That sentence may sound brutal, but it actually carries a form of certainty that, in its own way, is a privilege. Many people go through life without knowing their limits, without knowing what their body has in store for them, without having a name for what holds them back. I know. I know exactly what I have, why I have it, and what it means. There is a kind of clarity in that which, even on the hard days, helps keep moving forward.

It's not always visible, it's not easily understood, and it wears you down in silence.

This text is the first in a series in which I will tell the story of my journey toward deep brain stimulation, from the surgery to the difficulties to the results. But before talking about what changed, I need to say what it was like before. What it's like, day after day, to live in a body that doesn't respond the way it should.

Two problems in one

Myoclonus-dystonia is a double burden -- two symptoms stacked on top of each other, feeding off one another.

First, the dystonia: involuntary muscle contractions that pull and twist. In my case, it's mainly the neck and trunk that are affected, with the left side of the body being predominant. It's not dramatic, not the kind of thing you'd notice from across the room. But it's enough that your posture is never quite straight, your neck is never quite relaxed, your body is never quite at rest. It's a permanent background tension, like a constant hum you eventually integrate but that never switches off.

Then come the myoclonias -- brief, involuntary, unpredictable jerks that occur mostly when I try to do something precise. The hand that shoots off when aiming, the arm that jolts when holding something. It's the left side that's most affected, but the trunk and upper body in general don't get off easy either. And the cruelest part is that it gets worse with stress, fatigue, or the simple act of trying to do well. The harder you try to control it, the more it escapes. The body does exactly the opposite of what you ask it to, at the precise moment you need it most.

There's also the tremor, which isn't a regular tremor like you sometimes see in elderly people, but a myoclonic tremor -- irregular, erratic, varying from one day to the next. Some days it's almost absent, other days it's impossible to ignore, and there isn't always any apparent logic between the two.

The stolen gestures

The problem with myoclonus-dystonia isn't one big visible handicap that jumps out at you. It's more of a silent accumulation of small impossible gestures -- things everyone does without thinking that I cannot do, or at least not normally.

Brushing my teeth, for example. I need two hands: one for the brush, one to stabilize, otherwise the brush goes elsewhere and the movement becomes uncontrollable.

Cutting my toenails is impossible to do alone. The precision required, the body position, the coordination between both hands -- everything works against me at once.

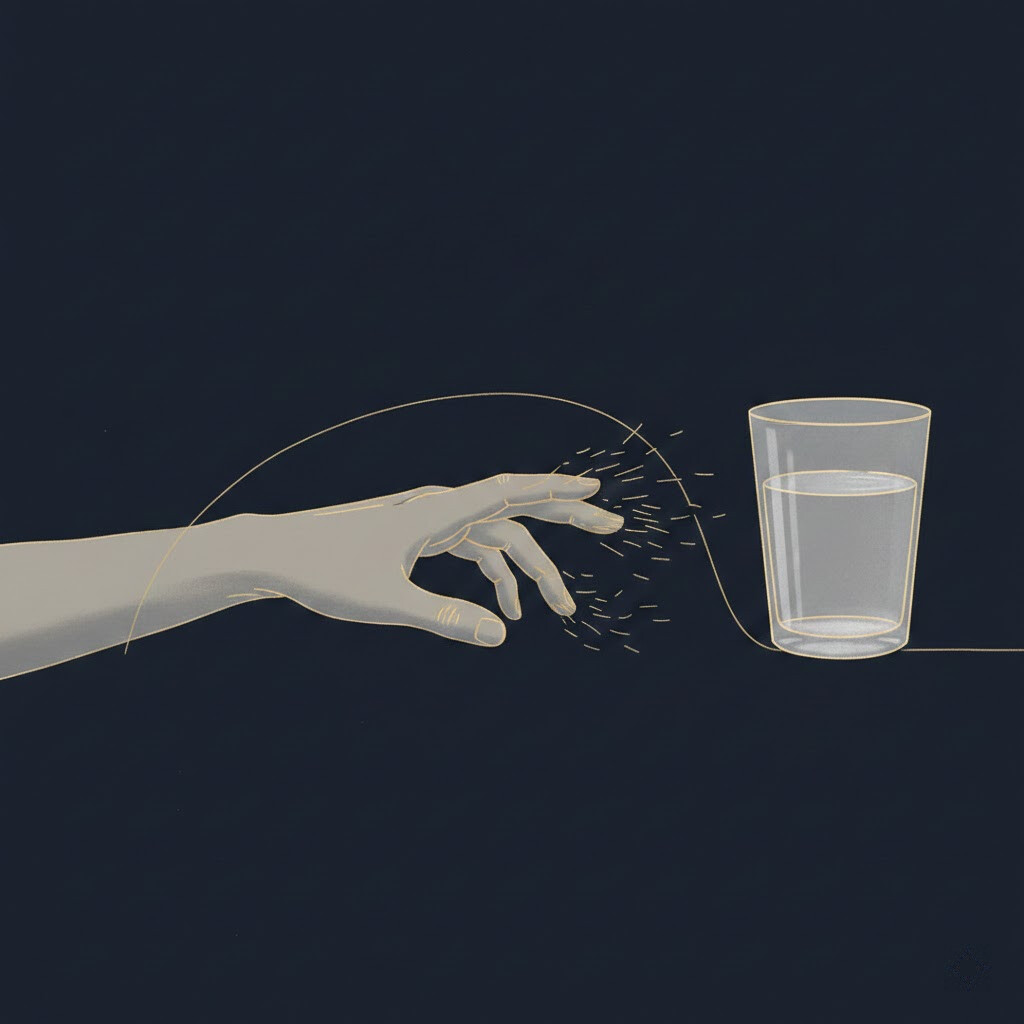

Pouring water into a glass looks like a trivial gesture, but I have to set the glass down, brace the bottle, and anticipate the jerk. If I do it standing up, arm outstretched, the way anyone would naturally do it, the water ends up on the side.

Writing is a battle in itself. Holding a pen, controlling the stroke, keeping a straight line -- all of that demands a disproportionate amount of concentration for the gesture. Carrying objects too, because you have to anticipate the jerk, compensate for the imbalance, and constantly adjust your grip. Going down stairs can become an ordeal when the myoclonias decide to show up at that moment, because the body needs stability and coordination -- exactly what the disease takes away.

And there's everything else. Eating neatly on some days, buttoning a shirt when fatigue is there, carrying a coffee without spilling it. Every daily gesture becomes a negotiation with a body that has its own plans, and that negotiation never stops.

What people don't see

The hardest part isn't the failed gesture itself. It's the enormous energy you spend making sure it doesn't show. It's the constant anticipation, the mental calculation before every movement, the unrelenting vigilance. Over time, you develop strategies, compensations, workarounds. You learn to set things down before letting go, to sit down before it kicks in, to avoid situations where the tremor would be too visible. It becomes second nature, but it's an exhausting second nature.

Stress is this disease's worst enemy, because it feeds directly on it. The more you stress, the more you shake. The more you shake, the more you stress. The circle is perfect and has no exit, and it takes considerable inner discipline to learn to break it -- or at least not to fuel it.

Fatigue also weighs enormously. Myoclonias are involuntary muscle contractions -- work the body does without being asked. It spends energy all day long on involuntary movements, and by the end of the day, you're exhausted without having done anything more than everyone else. It's a fatigue no one sees and few people understand, because it doesn't correspond to anything visible.

DYT11

A word about the disease itself. DYT11 is a code, and behind that code is a gene called SGCE, carrying a hereditary mutation. It's rare. Rare enough that most doctors have never seen a single case in their entire career. Rare enough that diagnosis can take years, because the symptoms look like other things and few specialists think to look in this direction. Rare enough that when you search for personal accounts online, you find almost nothing, and you end up alone facing a disease that nobody around you has ever heard of.

That's also why I'm writing these posts. So that the next people who search will find at least one voice, one journey, something concrete to hold on to.

There is no medication that truly works against myoclonus-dystonia. The myoclonias resist just about everything thrown at them. One option remains, the only one that has proven effective in genetic forms like mine: deep brain stimulation. Electrodes implanted in the brain, a device under the skin, continuous current sent into the basal ganglia to calm what's malfunctioning.

But before getting there, I need to talk about everything that doesn't work. Everything you try, everything you hope for, and everything that disappoints. That's the subject of the next post.

To be continued.